Jennifer Tynes

Saratoga, CA

jennifer

The Napalm Ladies

THE NAPALM LADIES

AKA “THE HOUSEWIFE TERRORISTS”

By Jennifer Tynes

Situated at the most southern part of the San Francisco Bay, the town of Alviso, California looks very much the same now as it did in 1966. Dilapidated structures bearing advertisements and logos for long forgotten businesses stand on the quiet streets lined with stucco and wooden houses where a small population still resides.

Like most of California, the original inhabitants were Indians who farmed in the fertile valley between the Santa Cruz and Diablo Mountain Ranges until a land grant was given in 1838 by Mexican Governor, Juan de Anza, to Ignacio Alviso. When settlers discovered that the mouth of the Guadalupe River running through San Jose emptied into the bay, it led to the creation of the town that became a major commercial shipping point between San Jose and San Francisco.

Alviso grew into a prosperous and thriving port where steamships docked at the busy wharves to transport passengers and take on cargo that included hides, tallow, grains, redwood timber and quicksilver from the New Almaden mines. The town was officially incorporated in 1852 and enjoyed prosperity until the completion of the San Francisco to San Jose Railroad in 1864 which bypassed Alviso entirely.

One hundred and two years later, many people living in the adjacent communities of San Jose and Milpitas had never heard of Alviso and fewer had actually been there. The town had descended into near obscurity with only a small number of businesses still in operation that were mostly industrial in nature. There was a post office, a grocery and several restaurants frequented by locals only with one exception, Vahl’s, which advertised fine Italian dining. Many of the buildings that had been abandoned long ago such as the Bayside Canning Company still stood, silent and empty, along the muddy wetlands and salt ponds once managed by the Alviso Salt Company. It was a perfect place to store bombs.

In May 1966, the United States was deeply engaged in a popular war being waged in Vietnam. Americans embraced concepts such as the domino theory believing that communism would spread from country to country and that aggression must be stopped before it escalated. The minority sentiment of anti-war activism was disdained and dismissed as crackpot liberalism considered un-American and pro-communist and only perpetrated by long haired, unkempt and dangerous people who burned flags and resisted the draft.

On May 16th, 1966 the San Jose Mercury News published a story covering an anti-war protest at the Washington Monument with a headline reading, “Thousands Protest U.S. Role In Viet War”; the accompanying story characterized the demonstrators as “a ragtag contingent of beatnik types displaying Viet Cong banners alongside American Flags”.

The following day, the newspaper covered another anti-war protest, this time much closer to home in Redwood City, California twenty miles north of Alviso. The headline read, “Human Bulwark Fails to Halt Napalm Truck”. A photograph with the story is captioned, “Bearded protester Aaron Manganiello, 23, lies in front of delivery truck attempting to enter Napalm factory at Port of Redwood City Monday”. Manganiello was arrested for creating a public nuisance along with local psychiatrist, Oliver Henderson, a former member of the San Mateo County Health and Welfare Department who had been removed from his position for refusing to sign a loyalty oath. Confronted by Police Chief William Faulstich and informed that he and his group of protesters were breaking the law, Henderson shouted, “We’re trying to uphold a greater law.” The police chief made the insightful comment that the incident was a publicity stunt.

Two months earlier, a group of concerned citizens had been unsuccessful in their attempt to prevent the Port of Redwood City from leasing two acres of city property to United Technology, who was under contract with the Department of Defense to manufacture 100 million pounds of napalm. The Port Commissioners met to consider the lease application and during the meeting, the chairman was forced to allow public comment from the floor and set ground rules that speeches be limited to two minutes and that moral issues would not be open to consideration.

Ignoring the chairman’s warning, local resident, Olive Mayer, spoke eloquently about her reaction to the sight of the Belsen gas ovens designed by her fellow German engineers who calculated how many victims could be executed at a time according to ingress and egress. “Local government and professional people had to be involved in providing for locations for the manufacture of these ovens, just as you commissioners are now called upon to make a decision concerning a napalm factory,” she stated. When Stanford English Professor, Bruce Franklin, spoke about how napalm was being used on innocent civilians in Vietnam, the chairman with the rap of his gavel ordered, “Get that man out of here!”

The use of fire bombs dates back to the Romans who hurled streams of flaming liquid at their enemies but a team of Harvard chemists led by Dr. Louis Fieser in a competition sponsored by the government are credited with inventing napalm in 1942. Incendiary bombs made with aviation gasoline had been in use in warfare for decades but due to its rapid dispersal, gasoline was eventually deemed unsuitable. Experimentation with thickeners that were added to gasoline produced desired results; an extremely flammable substance that looks like bee’s honey with the consistency of a sticky jelly that adheres to and incinerates whatever it comes into contact with including human flesh. Napalm burns with such a hot intensity that all oxygen in the surrounding area is exhausted within seconds and death occurs either by suffocation or being burned alive.

United Technology planned to manufacture a newer version, napalm-B, at the Redwood City location and in the cramped port manager’s office, where only a small number of protesters managed to squeeze in, the port commissioners, with the city attorney’s blessing, approved the lease. Production began immediately.

But public awareness of napalm use on civilians in Vietnam was increasing and reports began to surface with startling estimates of casualties numbering in the hundreds of thousands. Slowly the image of the anti-war activist began to change as members of academia and other respected professions became involved and attempted to educate others about what they felt were atrocities being committed against innocent people in an illegal war. One of them was Francis Heisler, a Hungarian born electrical engineer who came to the United States in 1924, studied law, and spent more than fifty years dedicating his efforts to protect civil liberties. A champion of the weak and powerless and first amendment rights, Francis Heisler defended over two thousand conscientious objectors and draft resistors.

Heisler was an advocate for civil disobedience as a means of protest. During a speech at a meeting of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) held in Berkeley, California in the spring of 1966, he discussed the strategy in the context of personal responsibility. Two members of the San Jose WILPF chapter, Aileen Hutchinson and Joyce McLean, attended the meeting and like Heisler, the women represented a departure from the stereotypical anti-war activist.

Aileen Hutchinson had moved to San Jose from Washington DC where she had been active in the Women Strike for Peace (WSP) movement, a group founded in 1961 to protest nuclear testing. WSP members were mostly middle-class, informed women with children who presented their concerns in the context of motherhood. There was not a WSP chapter in San Jose, so Hutchinson joined the local WILPF group. She was married to a former professor of economics at San Jose State, Dr. Bud Hutchinson, who was fired along with another faculty member for protesting the denial of admission to a black student from Alabama alleged to have been involved in a sit-in demonstration.

Highly educated and keenly intelligent, Joyce McLean joined WILPF while living in Australia after learning about the mistreatment of its aboriginal population. When she and her family returned to the United States in 1962, they moved into a San Jose neighborhood near the IBM facility where her scientist husband worked and every house on the block was full of kids. A newspaper dropped at her doorstep carried a notice of an upcoming WILPF meeting which she attended and the already busy mother of five children became involved immediately.

WILPF members dedicated most of their efforts to promoting peace which meant being anti-war and according to McLean, they felt it was a full time job to try and educate others. Her opposition to pro-war sentiments invited relentless criticism and she encountered unfriendly glances at her son’s little league games, but she steadfastly held to her belief that “we are carefully brainwashed, my country right or wrong instead of my country when wrong should be set right”.

McLean joined other women on a weekly basis, carrying protest signs and holding anti-war vigils every Thursday in front of the draft board building in San Jose where they attempted to distribute leaflets to people who looked away and mostly ignored them. They experimented with different types of leaflets that adopted holiday themes to attract more attention and joked that when the war ended, they would all work for the Hallmark card company. They performed a version of street theater for people going to and from their lunch breaks, one time McLean dressed as a general smoking a cigar, another dressed as a nurse, still another carried a baby doll as they encouraged passersby to join the anti-war effort with little apparent success.

But on occasion, there would be a rare individual or two who would linger behind their companions on the sidewalk and when they thought no one was looking would whisper, “You know they talk about you all the time.” It was enough to offer encouragement.

WILPF members discussed many topics and began to focus on the use of napalm in Vietnam. They gathered and shared information from newspapers and magazines including articles in The Ladies Home Journal that described the horrific effects of napalm and depicted photographs of burned children that appeared side by side with cosmetic advertisements and recipes. The stories were distressing and alarming but also moved them to take action. Dow Chemical was known to be a major supplier of napalm and the women began to boycott all products manufactured by the company including cleansers and Saran wrap.

They felt the use of napalm on innocent civilians in Vietnam was illegal, and after hearing Frances Heisler speak, Hutchinson and McLean were even more inspired to take action. On the drive home from Berkeley, they discussed various options and decided that civil disobedience would suit their purpose and began to make plans to interfere with and prevent shipment of napalm bombs to Vietnam. It was a lofty objective, two women who were wives and mothers contemplating physical intervention against a war machine backed by the United States Government and hoping the stone they would sling would find a hole in the armor of the giant.

Through contacts involved in anti-war efforts, they women learned that napalm bombs manufactured at the United Technology facility in Redwood City were trucked to a warehouse in San Jose for temporary storage and then moved to Alviso where they were loaded onto barges and shipped to Port Chicago for ultimate delivery overseas. The secret was out.

The San Jose Mercury News reported, “Alviso Stores Viet Napalm” and that huge stockpiles of wooden crates packed with shiny gray cylinders containing the jellied gasoline were being temporarily stored at the Port of Santa Clara County on the Alviso Slough. A partner in the local trucking firm hired to store and move the bombs had been successful in convincing city planning commissioners and the fire marshal that the presence of the bombs did not pose a danger to the surrounding community.

The plan to engage in civil disobedience to protest the use of napalm began to take form and joining the planning process was another WILPF member, Beverly Farquharson. Quiet but with a sharp sense of humor, Farquharson was a mother of two who had been active in anti-war protest events and demonstrations for years. WILPF meetings were held at the San Jose Peace and Justice Center where she, Hutchinson and Mclean were introduced to Lisa Kalvelage, a woman with a unique and very personal connection of her own to anti-war and peace efforts.

Kalvelage was born in Nuremberg, Germany, a heavily bombed target during World War II. When Hitler refused surrender, the Allies’ bombing raids were expanded from military and industrial sites to heavily populated cities including Nuremberg where she spent her teenage years hungry, cold and scrambling into the basement for cover. The experience left her with a feeling of guilt that the German people had done little or nothing to stop the atrocities committed by the Nazis even though she was just a girl at the time. She was quoted as saying, “Once in a lifetime is enough for me” and vowed that unlike her own parents who silently stood by, her children would know that she was a woman who spoke up and took action.

The women had no idea what the outcome of their efforts would be, or that with the passing of time, their actions would ultimately be considered heroic. What they did know was, the possibility existed that they might be arrested and serve jail time. As they made plans to form a picket line at the trucking facility in San Jose, they also conferred with lawyers who led them to believe that if arrested and convicted, their sentences could be as long as six months. Undeterred by this ominous reality, they made final preparations that included arrangements with family and friends to care for their children.

One can only imagine the scene in each household when it was explained to their children who ranged in age from four to nineteen years old, that Dad, the babysitter or maybe they would be making dinner and washing clothes if their mother went to jail. Only two received support and encouragement from their husbands, and one feared for his wife’s physical safety and his own public image. Beverly Farquharson confessed that what she feared most was not jail, but the other jail mates yet she was later described as being the bravest of the four.

Defying the image of the typical anti-war protester, the women knew it was important to perform their acts of civil disobedience in a dignified and ladylike manner. In McLean’s words, “We dressed to the hilt, heels, pearls, gloves, like ladies at a garden party”, and in the early morning of May 24, 1966, they joined other women to form a picket line at the Duodell Trucking Company in San Jose where napalm bombs were stored before being moved to Alviso.

The women assembled and took their position on the line, each of them setting aside the fear of facing down a truck that might not stop and what those consequences would be. As they stood in front of the trucking company holding their picket signs, trucks arrived and parked down the street. The drivers got out, each carrying a fist full of paperwork, entered the trucking office then returned to their trucks and left. Along with the media who had also shown up, the trucking company had been alerted by FBI informants in advance of the protest and was ready for them. The event made the evening news.

They returned the next day and were told there would be no trucks or deliveries as long as the picketers were present. The decision was made to drive to Alviso where another stockpile of bombs were waiting for shipment and block the loading operation. Hutchinson, McLean and Farquharson joined Kalvelage in her car and headed for the once thriving port of Alviso that had been reawakened and was active again; only this time instead of hides, timber and silver, the cargo was deadly napalm bombs.

Again, the foursome had donned their garden party and ladylike attire and in addition to their handbags, they carried signs. The messages read “Would Napalm Convert You to Democracy?”, “Napalm Kills People Not Communists”, “Children Were Born to Be Loved Not Burned” and “I Don’t Want to Be a Murderess”. They parked the car on a dusty road adjacent to the water where gentle waves lapped against the marsh and mud then walked around a locked gate, passing a “No Trespassing” sign along the way. They trudged up a dirt incline, struggling in their high heels until they found themselves surrounded by hundreds of neatly stacked shipping crates full of bombs.

A forklift was busy loading the bombs onto a waiting barge and to the astonishment of the driver, the four ladies boldly stepped in front of the vehicle, informed him that what he was doing was immoral and demanded that he stop. The forklift driver’s astonishment quickly turned to fury and as he climbed down, he shouted to them that he was calling the police. The police turned out to be Chief Arnold “Pat” Chew, a man born and raised in Alviso and then serving as the town’s first and only Chief of Police. Chief Chew had been summoned from a morning coffee break; it was rumored that he took his breaks in the bar of Vahl’s restaurant.

When Chief Chew arrived, the driver returned, climbed back onto the forklift and started driving directly toward the women when Lisa Kalvelage dropped to her knees into the dirt and the others stood their ground. The valiant police chief pushed Kalvelage aside, stepped between the women and the advancing forklift and ordered the driver to stop. “Get off! Immediately!” he yelled to the driver and threatened to arrest him.

Angry that the police chief took the side of the women, the driver uttered a few profanities and stomped away, yelling over his shoulder, “I’m going to get my dog!”

Reinforcements showed up in the form of a county sheriff and two deputies who were uncertain about how to proceed and eventually the man who had the permit to store and move the bombs arrived. The sheriff informed him that he would have to press charges against the women if he wanted them to be arrested and instead, he begged them to leave.

“But how can I face my wife if I have you arrested?” he asked.

“How do you face your wife when you do this horrible thing every single day?” they replied.

As the cadre of law enforcement personnel went into a huddle with the man holding the permit to determine what to do, the forklift driver returned with a ferocious German Shepherd and threatened to attack the women. They called out, “Hey guys!” and pointed to the man and his dog who were promptly thrown off the property.

It was finally determined that the women had broken the law and they were arrested. The ladies were polite and cooperative although there was disagreement among themselves and the arresting officers regarding how much information they had to provide. McLean refused to give her age and Hutchinson declined to give her name. Female deputies arrived to escort them to jail and asked if the women were willing to walk to the squad car and they answered, “We were blocking bombs, not defying local police”. The female deputies promised to take good care of their signs.

The Elmwood Jail in Milpitas, California is approximately six miles from Alviso and is operated by the County of Santa Clara Department of Correction. When the Napalm Ladies, the shared moniker the newspaper later assigned them, arrived at the jail, they were taken to a booking room to fill out paperwork, then to another room where they were strip searched, given tubes of Prell shampoo and told to shower and wash their hair. Later accounts reported that Kalvelage was especially upset about the hair washing since she had just been to her hairdresser.

The women were given jail outfits and served baloney sandwiches for lunch. Fully expecting to spend the night, they were surprised to learn that their arraignment would take place that day and were given bulky cardigan sweaters to wear in an effort to improve their appearance in the unflattering jail clothes. McLean was allowed to wear her hat.

A friend and co-founder of the San Jose Peace and Justice Center, Barby Ulmer, made arrangements to retain an attorney to represent the women at the arraignment, although they were prepared to represent themselves. Reed Searle, a former public defender who frequently took cases for conscientious objectors and draft resistors, was recruited and agreed to offer his services pro bono. Self-described as a “young left winger”, Searle appeared on their behalf, took on their cause with zeal and was able to have them released on their own recognizance that afternoon.

The next day, the Mercury News carried a story with the headline, “4 Napalm Pickets Arrested” and provided details about the confrontation between the women and forklift truck operator, Roy Marshall. There was no mention of Mr. Marshall’s threats or the dog, but Chief Chew stated that when one of the women had dropped to her knees in front of the forklift, “I wasn’t about to go through this, I called for help from the sheriff’s office.”

The reaction to the event from family, neighbors and co-workers was mixed and mostly unfavorable. McLean’s Leave it to Beaver neighborhood transformed into one where people would not make eye contact with her and whispered to each other that the family must be communists. A boy across the street shouted “Protester!” whenever he saw her. Douglas, her soft-spoken articulate chemist husband, served her champagne to toast her courage but also starting eating lunch at his desk at IBM instead of with his war supporting colleagues. Her father was unhappy that his daughter had made a spectacle of herself on the news but expressed his relief that at least she was well dressed at the time of her arrest.

McLean made the news again just a few days later when she was invited to speak at a major napalm protest event organized by local peace organizations that took place in Redwood City on May 28, 1966. Headlining the event was Wayne Morse, who along with Ernest Gruening, were the only U.S. Senators who opposed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that authorized President Johnson’s massive escalation of the war in Vietnam.

Starting at Sequoia High School, demonstrators marched two miles to the United Technology Center, their numbers swelling to more than 2,000 as they passed hecklers and received a cold reception from downtown merchants that displayed American Flags and signs supporting the war. Local newspapers characterized the protesters as “Vietniks, beatniks and peaceniks”.

Tom Wicker, the Washington Bureau Chief for the New York Times was also in attendance to cover the event. Demonstration organizers arranged for Joyce McLean to march next to him and for two miles they engaged in a spirited discussion about her arrest and the impending trial. Wicker was so taken by her impassioned position and impressed by the willingness of ordinary women to go to extraordinary lengths to promote their beliefs that he soon reversed his position and became an outspoken critic against the Vietnam war.

Back at home in San Jose, events were heating up as the women prepared for their trial. The Mercury News ran a story headlined “Anti-Napalm Women Will Answer Trespass Charges” but ironically, the women had not been charged with trespassing. The Deputy District Attorney, Keith MacLeod, had decided to charge them with interfering with a lawful business, a charge that inspired an interesting and unusual defense strategy.

Violation of California Penal Code Section 602 is considered a misdemeanor and covers a wide array of possible transgressions. Punishable offenses include entering land to gather and carry away shellfish and oysters without a license, maliciously tearing down and mutilating signs, skiing in areas closed to the public, building fires and discharging a firearm. Hutchinson, McLean, Farquharson and Kalvelage were charged with Section 602J, “Entering lands, whether unenclosed or enclosed by fence, for the purpose of injuring any property or property rights or with the intention of interfering with, obstructing, or injuring any lawful business or occupation carried on by the owner of the land, the owner’s agent or by the person in lawful possession”.

There was speculation that the Deputy D.A. was copying another high profile case in San Francisco where civil rights demonstrators had staged a sit-in at an upscale automobile dealership and were charged with interfering with a lawful business. Defense attorney, Searle, planned to argue that there is a difference between what is legal and what is lawful, the word legal defines what is permitted by law and the word lawful means in harmony with the law, natural or manmade, and carries a moral implication.

Originally, the defendants had planned to enter pleas of nolo contendere because they thought it would be the easiest until word of the trial and their intentions reached Frances Heisler, the very same man who inspired Aileen Hutchinson and Joyce McLean to perform the act of civil disobedience that landed them in a courtroom. When he learned that they had been charged with interfering with a lawful business, he gleefully announced, “I’ve waited ten years for a case like this,” accepted Reed Searle’s invitation to join the defense team and convinced the women to enter pleas of not guilty.

The trial got under way on Monday, June 20, 1966 in the Municipal Court for the San Jose-Alviso-Milpitas Judicial District in the County of Santa Clara and was presided over by the Honorable Judge Edward J. Nelson. The defendants entered the courtroom carrying flowers given to them by well wishers and the signs they had carried during their protest had indeed been taken care of as promised and were on display in full view of the jury box.

Deputy District Attorney McLeod called his first witness, Alviso Chief of Police Pat Chew, and asked him provide his account of the event that took place on the property of the Port of Santa Clara the morning of May 25th. Chew testified that the women had blocked operations by standing in front of a fork lift used to convey napalm bombs to a loading platform and that by occupying the only ramp leading to the platform they brought loading to a halt. Sheriff Deputies Robert Jorgenson and Gail Stroud also testified and stated that the women refused their repeated requests to leave the property and to do their picketing elsewhere. “I got the impression they wanted to be arrested,” Stroud testified.

The day ended with Searle promising that all four women would testify in their own defense the following day and that a major part of their defense would rest on “the applicability of international law to the case”.

The trial ensued the following day. Reed Searle addressed the court and announced the association of Frances Heisler then called his first witness, Joyce McLean. After providing minor details such as her address, the ages of her five children (McLean never did have to divulge her age, 32, at the time of the trial) a humorous exchange between attorney and client took place regarding a gate they encountered that was unlocked at first and locked after their arrival.

“Did you climb over the gate?”

“No.”

“Did you walk on the water without getting your feet wet?”

“No.”

“How did you get into the property then?”

“There’s a not too steep incline and it was very easy to walk around the gate.”

When asked what their purpose was for entering the property, McLean testified they intended to interfere with the unlawful business of napalm bombs. Asked if she thought they were breaking the law, she confirmed again, “No sir, we went to stop an unlawful business.” She described her other efforts to promote peace and end the war; picketing, demonstrating, writing letters and standing in vigils to no avail and said, “I believe the horror is just increasing so there was nothing to do but to physically attempt to stop it.”

Searle asked if she believed that the use of napalm was a sufficient reason to break the law and to define what unlawfulness she was attempting to stop. Her answer, that bombs were being dropped on villages and people, was immediately challenged with an objection by Deputy D.A. McLeod, “She is testifying under oath here, testifying not what she knows and contends, but only what she’s heard through other means of possible propaganda.” Judge Nelson overruled him and allowed McLean to answer. She concluded her testimony by saying that she had not personally seen bombs being dropped but from all accounts she had heard and read, she believed it was true and that she did not break the law.

Searle’s next witness was Lisa Kalvelage who also provided minor personal details; her address, she was the mother of six children and had become an American citizen in 1953 after emigrating from Germany. She also confirmed that she was carrying a sign when she was arrested, “I carried this one,” she said pointing, “about children and people not allowed to be burnt. Number two.” He asked why she had gone to Alviso, she answered, “Because I felt morally compelled to go out there and stop something which I believe is another war crime. I was obeying the law that I have a moral obligation to stop crimes when I believe crimes are committed.”

Kalvelage’s testimony was riveting and emotional and when given an opportunity to explain why she felt she had a moral obligation, she replied, “One of the reasons is that I have lived in Nuremburg during the trial and it was hammered then into my head over ten months every day on the radio that not only the people, the defendants are guilty, but every German is guilty because they have not spoken up about crimes against humanity when they knew about it and nobody can hide behind the abstract idea it was my government, because you are the government and you have to take responsibility.”

Acknowledging that she was just a teenager during the war and barely twenty one years old at the start of the trials, she went on to say, “But I still can’t get rid of the feeling that I have to take the burden of mass guilt which all Germans are charged with and I came to the conclusion that once in a lifetime to be charged with a mass guilt is enough. I cannot take it a second time and I would do anything to protest and show that I have nothing to do with what is happening right now in Vietnam.”

Kalvelage recounted how she had been initially denied an exit visa from Germany to join her future G.I. husband in the United States because the answers to hypothetical questions posed to her did not indicate that she had learned the lesson of personal responsibility. When Searle asked her to define what personal responsibility meant, Deputy D.A. McLeod vigorously objected to her testimony stating it had no bearing and was immaterial to the case. Judge Nelson overruled him again.

She answered, “That at any price I have to follow my personal convictions without regard. If I feel that something is wrong, I cannot hide behind someone else under pressure and give up. I still have to stick to whatever I believe is right.” Like McLean, she testified that she had engaged in other forms of protest such as sending letters and telegrams and dedicated what little spare time she had to peace work.

Kalvelage testified she had been asked many times about what happened in Germany and if she or her parents had done something to protest those actions. “My parents didn’t do anything. Of course we lived under a dictatorship and I’m sure anybody that would even have spoken up in the slightest would have a similar fate as the Jewish people had, but I know this is a country where I can protest and I must protest and I don’t want it happening to my children that maybe twenty years from now somebody might charge this country with war crimes and people will say to my daughters, ‘Where was your mother, and where was your father when this happened? Didn’t they have anything to say?’ This was probably the last point when I decided to do this protest.”

McLeod’s cross-examination was brief. He asked if she entered the lands with the intent of interfering or obstructing with the business of the Port of Santa Clara County, she answered, “Yes, with the unlawful business conducted there.”

Beverly Farquharson was next and was asked to identify which sign she had carried at the protest. “I carried the sign which said ‘I don’t want to be a murderess’” Searle asked why she entered the property and she answered, “I planned to get to where the bombs were being unloaded from the barge and to stop the operation of this business which I considered to be unlawful, which I know to be part of a war crime, a part of the entire war which I considered to be unconstitutional.” He asked about her children. Farquharson had two, a daughter who was eighteen and a son nineteen who was in the Marines and stationed at Camp Pendleton, California.

Further questioning revealed that Farquharson’s son had not enlisted in the marines and that he was drafted. “What did your son’s being in the Marine Corps have to do, if anything, with your decision about …?” Searle was interrupted by her answer.

“I have seen pictures of members of our U.S. Marine Corps setting fire to Vietnam villages and I know if my son, if he goes to Vietnam, will be ordered to do these things which are, will be, of course, a violation of his conscience and against everything I taught him in regard to respect for law and order, his constitution, the supreme law of the land. That’s why I feel that I had to do what I did.” She emphatically denied breaking any laws adding that, “I have not been asked if I wanted to raise my son to be in a war which is illegal, a war in which napalm is used and therefore illegal too, because it also violates the humane the so called articles on humane warfare, because it is used intensely against civil families just like ours.”

McLeod began his cross-examination of Farquharson by asking her if she had observed the no trespassing sign. She quipped, “I saw several signs on the gates. One was ‘Keep Out’, and ‘No Trespassing’ and ‘No Smoking’. I was most impressed by the ‘No Smoking’ sign.” He posed the same rehearsed question, had her intention been to interfere with and obstruct the business of the Port of Santa Clara. She answered, “I entered the land, the lands of the Port of Santa Clara County to stop murder and if that interfered with the unlawful business going on there, yes.”

Aileen Hutchinson was the last defendant to take the stand where she provided her name, address and the ages of her two daughters. Defense attorney Searle began his examination by asking, “Mrs. Hutchinson, were you one of the four people that went out on May 25th to engage in the biggest crime wave in the history of Alviso?”

After waiting for laughter from the spectators to subside, she answered, “Yes,” and explained that their purpose had been to stop the transportation of napalm which is “the symbol of everything the United States is doing criminally and illegally in Vietnam. All of a sudden napalm was in our backyard. So our consciences began to bother us, at least mine did, and I felt I had to do something about it.” She admitted they obstructed the passage of the forklift and had observed and ignored a “No Trespassing” sign. “Something like a ‘No Trespassing’ sign should never deter one from trying to invoke a higher law to stop criminal acts.”

She testified that genocide is the most inhumane and atrocious of all acts and that is what napalm is used for, “Whether you agree with the war or not, whether the United States should be there, certainly, napalm is not used to win the war, it is used to obliterate the people. It has no purpose in winning a war, the only purpose is to kill.” She denied that they had interfered with a lawful business, “By no stretch of the imagination could it be considered lawful.”

During his brief cross-examination, Deputy D.A. McLeod could not muster any originality and asked Hutchinson the same question about interfering with the business of the Port of Santa Clara. Her simple one word answer, “Yes.”

The final witness for the defense was Donald Duncan, a former member of the Fifth Special Forces Group in Vietnam, more commonly known as the Green Berets. He was asked to testify regarding his observations of the use of napalm during his tour of duty and he stated, “The effect is quite devastating.” When asked if it killed people, he answered, “Of course,” and described how it kills people. In addition to burning victims, “The fire is so intense and so abrupt, in other words, it is from nothing to a fireball and no fire to a huge fire. It of course, does rob oxygen from the air and can also cause collapse of the lung.”

McLeod asked the Vietnam veteran only two questions; was he ever captured by the Viet Cong and “Did you come into contact with supposed communists at that time?” Duncan answered that he came into contact with people with weapons in their hands and “inasmuch as we were shooting at each other” and Viet Cong are communists, the answer was “Yes.”

The witness was excused, the defense rested, but the most important part of the trial was yet to come. Heisler and Searle were allowed to argue in chambers with Judge Nelson and successfully convinced him that the defendants were protected by three legal doctrines that should be introduced into the trial. The lawyers cited the Washington Treaty of 1922 that prohibits the use of poisonous gases and analogous liquids, the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 that renounced war as an instrument of national policy and the Fourth Principle of the Nuremburg Judgment of 1946 that states, “The fact that a person acted pursuant to an order of his government or of a superior does not relieve him from moral responsibility under international law, provided a moral choice was in fact possible to him”.

The trial resumed the next day. Final arguments were presented to the jury that consisted of six women and six men; Antoinette Battaglia, Frances Delp, Gordon Ervin, Douglas Hodges, Mary Hoffman, Kin Lee, Luther Tomas, George Hiari, Mildred Jacobs, Minnie Kelliher, Helen Lewis and Salvatore Rositano. All twelve juror’s names and their addresses were published in the newspaper, several of them lived near the defendants.

Then it was Judge Nelson’s turn. In his instructions to the jury, he told them the defendants were protected by the laws of the United States and cited the Washington Treaty of 1922 that was signed by the United States, Great Britain, France, Italy and Japan. “You are instructed that by law of the United States, the use in war of asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases and all analogous liquids, materials or devices, having been justly condemned by the general opinion of the civilized world, are prohibited and unlawful.” He also cited the Kellogg-Briand Pact in which the United States renounced war as an instrument of policy and the Nuremburg judgment. The Honorable Judge Edward Nelson’s instructions to the jury were in essence to let the Napalm Ladies go free.

Judge Nelson’s actions were unprecedented and he knew he was ruling against popular opinion. But like other heroes in the story, he was willing to take a risk, interpret the law as he saw fit and follow his own conscience. He was later admonished by several members of the California state legislature and he was never advanced to a higher court position, remaining at the municipal level until he retired.

Jury deliberations did not last long. Completely disregarding Judge Nelson’s instructions and international laws, they returned within two hours with a unanimous verdict of guilty. After reading the verdict aloud to the defendants, the judge polled the jurors individually, each responded with “Yes” or “It is”, affirming the decision. When interviewed later, several jurors commented that they felt the women just wanted publicity and they got it. One member said she went along with the others because she was afraid they would turn on her and another stated he did not believe there was napalm in Alviso.

The women were sentenced on Friday, June 24, 1966 . Douglas McLean, who had been in attendance each day at the trial, was so angry with the verdict that he refused to go. The women were given a ninety day jail sentence, a $110 fine and placed on formal court probation for a period of two years with the condition that they obey all laws. The jail sentence and the fine were immediately suspended. The Mercury News reported, “Judge Nelson stated he felt certain the women were well convinced and sincere in their thoughts that they were protesting within the laws of this country. In imposing this sentence, the court has taken into consideration that the defendants did what they thought was the right thing to do.”

Laws can be interpreted and applied in subjective ways, especially when an individual has a strong conviction about what is morally right or wrong. On December 14, 1967 the Honorable Judge Edward Nelson granted a petition filed by defendants Lisa K. Kalvelage, Joyce E. McLean, Aileen A. Hutchinson and Beverly E. Farquharson to terminate their probation and set aside the guilty verdict. The Napalm Ladies were exonerated but their notoriety had continued to increase.

The publicity they were accused of seeking and attention generated by the arrest and trial was far more than anyone had imagined or anticipated, even reaching international radio and television broadcasts and newspapers. Reed Searle’s in-laws vacationing in Paris read about it in the international edition of The New York Times that carried the headline, “Foes of Napalm Convicted in U.S.”

Folk singer and fellow pacifist, Pete Seeger, was so moved by the event and Lisa Kalvelage’s story, he wrote two songs about the women and incorporated words from her testimony into one of them, “My Name is Lisa Kalvelage”, the last verse reads:

The events of May 25th, the day of our protest,

Put a small balance weight on the other side

Hopefully, someday my contribution to peace

Will help just a bit to turn the tide

And Perhaps I can tell my children six

And later on their own children

That at least in the future they need not be silent

When they are asked, “Where was your mother, when?”

Seeger’s other song, “Housewife Terrorists”, tells the story of what took place in Alviso and includes the following verse.

The owner said, Ladies, why don’t you think of your children?

We are, says we, and yours as well

And we’re thinking of those children in far off Vietnam

For whom these bombs will make a burning hell.

Taking risks, making personal sacrifices and having the conviction to follow one’s own moral compass when others are going in a different direction is never easy. These incredible women were willing to do all three to bring attention of the use of napalm and end the suffering of innocent people and their success can be measured in many ways. They discovered later that they had interrupted operations in Alviso long enough that the tide changed and the barge was unable to leave the port that day. The permit to store the bombs in Alviso was eventually revoked and shipment from the port ceased. New York Times reporter, Tom Wicker, after his encounter with Joyce McLean, reversed his pro-war position and became an active voice against the war.

Four mothers facing down a forklift loaded with bombs helped increase public awareness of the use of napalm and it became a symbol for genocide and the failure of American military power. The iconic Pulitzer Prize winning photograph taken in 1972 of Vietnamese children fleeing their burning village made the issue a visual and undeniable horror. But it would still take more than 36 years for the United States to sign Protocol III of the Treaty on Certain Weapons adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1980 that prohibits the use of incendiary weapons “designed to set fire to objects or to cause burn injury to persons through the action of flame, heat or combination thereof” on civilian populations or on “forests or other kinds of plant covers”. President Obama signed the protocol his second day in office in September, 2008.

Each of the Napalm Ladies left a unique legacy behind. Beverly Farquharson was credited with contacting folk singer and activist, Pete Seeger, and inspiring him to write and record the two songs. She passed away at the young age of forty-two from a liver ailment, a short four years later after her protest on the Alviso loading dock.

Although she maintained a close friendship with Joyce McLean, Aileen Hutchinson did not talk much about the arrest and trial in subsequent years and was always surprised when she met someone who remembered and praised her deed. She later moved to Mexico and was killed in a house robbery.

Lisa Kalvelage continued her involvement in anti-war movements and served as Coordinator of the San Jose Peace and Justice Center from 1967 to 1972. Along with her husband, Bernard, she attended peace rallies and protest marches well into her eighties and took a strong position opposing the war in Iraq. When asked during an interview in 2003 if opposition to the war in Iraq was unpatriotic, she answered, “Quite the opposite. The best thing we can do is bring the troops home. We believe the war was not necessary and our government put those young people in harm’s way.” She passed away in March, 2009 at the age of eighty-five.

Joyce McLean also remained committed to peace and anti-war efforts in spite of several serious and life threatening health issues including two bouts with cancer and a leg amputation that did little to slow her down. She also found time to volunteer and teach at night to English language learners and was elected to the Loma Prieta School Board and later removed for what she described as “trying to ram excellence down the throats of the community”. Along with hundreds of women from WILPF chapters around the world, she rode on a Peace Train from Helsinki to Beijing in 1995 and in 2003 at the outbreak of the war in Iraq became one of the “Capitola Thirteen” who were arrested for blocking the entrance to the recruiting station in Santa Cruz, California.

The episode in Santa Cruz was one of many taking place to protest the war in Iraq, but McLean’s involvement elevated it to a national and ultimately, an international level when her prosthesis fell off as she struggled in handcuffs to exit the van when they arrived at the police station. A news photograph depicts the then sixty-nine year old grandmother being escorted by SWAT team members dressed in full tactical regalia but instead of pearls, McLean was wearing a WILPF sweatshirt. The protesters were cited and released and the charges were dropped.

Alice Walker, author and peace activist, once said change is a relay race, “…our job is to do our part of the race, and then we pass it on, and then someone picks it up, and it keeps going.” A few years before her death, McLean referred to Walker’s term when she reflected on their efforts to bring about change, “Did we succeed in getting people to join us? Not then, but we planted a lot of seeds, we were part of The Relay Race that built a movement even though we didn’t end the war for years.”

Presently, the United States remains at war, rumors of napalm use persist and civilian casualties continue. The Napalm Ladies began their race in 1966 and it lasted for forty five years and not much has changed. Joyce McLean was the last one to pass the baton when she died on December 13, 2011; her legacy is to keep the race for peace going.

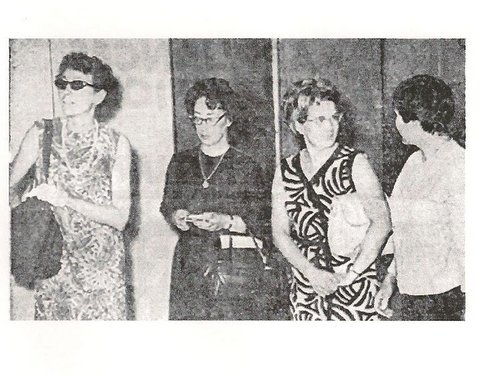

The Ladies

Joyce McLean, Aileen Hutchinson, Lisa Kalvelage and Beverly Farquharson.

Copyright 2012 Jennifer Tynes. All rights reserved.

Saratoga, CA

jennifer